Rsa Cryptography

The idea behind cryptographic communication is that it should be hard/impossible for eavesdroppers to decrypt the messages, but relatively easy for the intended recipient to decrypt.

For this to work at all in general, the recipient must know something that eavesdroppers don’t.

To build up to how RSA and communicating across an insecure channel works, we can first observe that there are a whole class of problems that are incredibly hard to solve, but easy to verify. These are NP-complete problems.

Integer factoring is an example of one such problem. What are the prime factors of 3788785476918598522485392151940648251? I’ll even give you a hint by telling you that it only has two prime factors.

To figure it out will take a bit of time. But if I tell you that its prime factors are 2004827797223529579 and 1889830878325638769, you could very quickly plug that into a calculator to confirm.

And ultimately, integer factoring is what underpins the security of RSA encryption.

Essentially, to encrypt a message “m”, we raise it to some power “e”, divide by some N, and keep the remainder as the ciphertext “c”.

In notation: m^e = c mod N

The security of this ultimately depends on two facts:

- modular exponentiation seems to output random results and you can’t simply reverse the procedure

- if you know the prime factors of the modulus, then you can invert the exponentiation, but it’s incredibly hard to find the prime factors of large numbers

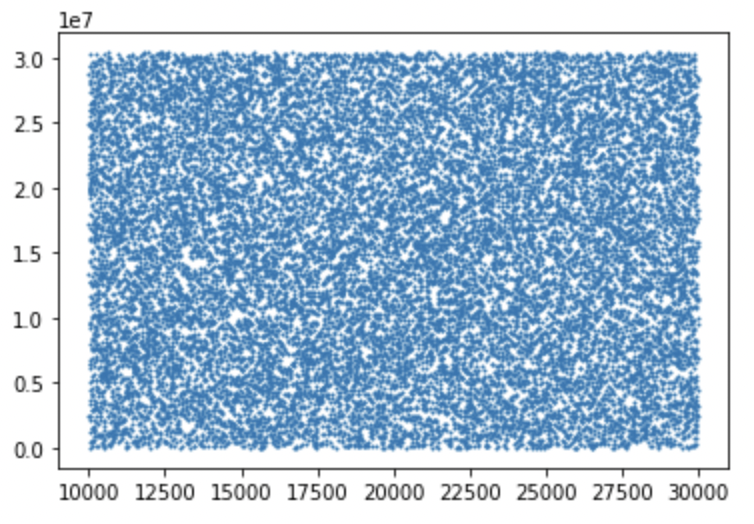

Applying y=x^e mod N for several thousand x with e=3 and N=30402457

To decrypt, we are looking for d such that c^d = m mod N. In other words, m^e^d = c mod N, or m^(ed) = c mod N

For this to be useful it needs to satisfy several constraints:

- c should be decipherable!

- this means d should be guaranteed to exist

- x^e = c mod N should have a unique solution of x=c^d. Otherwise the recipient can’t recover a unique message

- it should be hard for eavesdroppers to decrypt

- it should be easy for the recipient to decrypt

Finding such a d is not trivial under all circumstances. In fact, it might not even exist!

Note that exponents and logarithms behave very differently modulo some N, than they do normally. The algorithm for computing a discrete logarithm (in order to reverse the effect of m^e) essentially requires factoring the modulus N.

So before we can address how it’s possible for the recipient to decrypt c, while making sure it’s still hard/impossible for eavesdroppers, we have to prove that it’s even mathematically possible.

To make sure that we can find d satisfying c^d = m mod N we have to be specific when choosing N and e.

We already said that N should be a very large number that has two prime factors. So then how do we choose e?

We know that m^(ed) = m mod N, this means that m^(ed - 1) = 1 mod N

To move forward, we will have to take a bit of a detour.

Detour into number theory

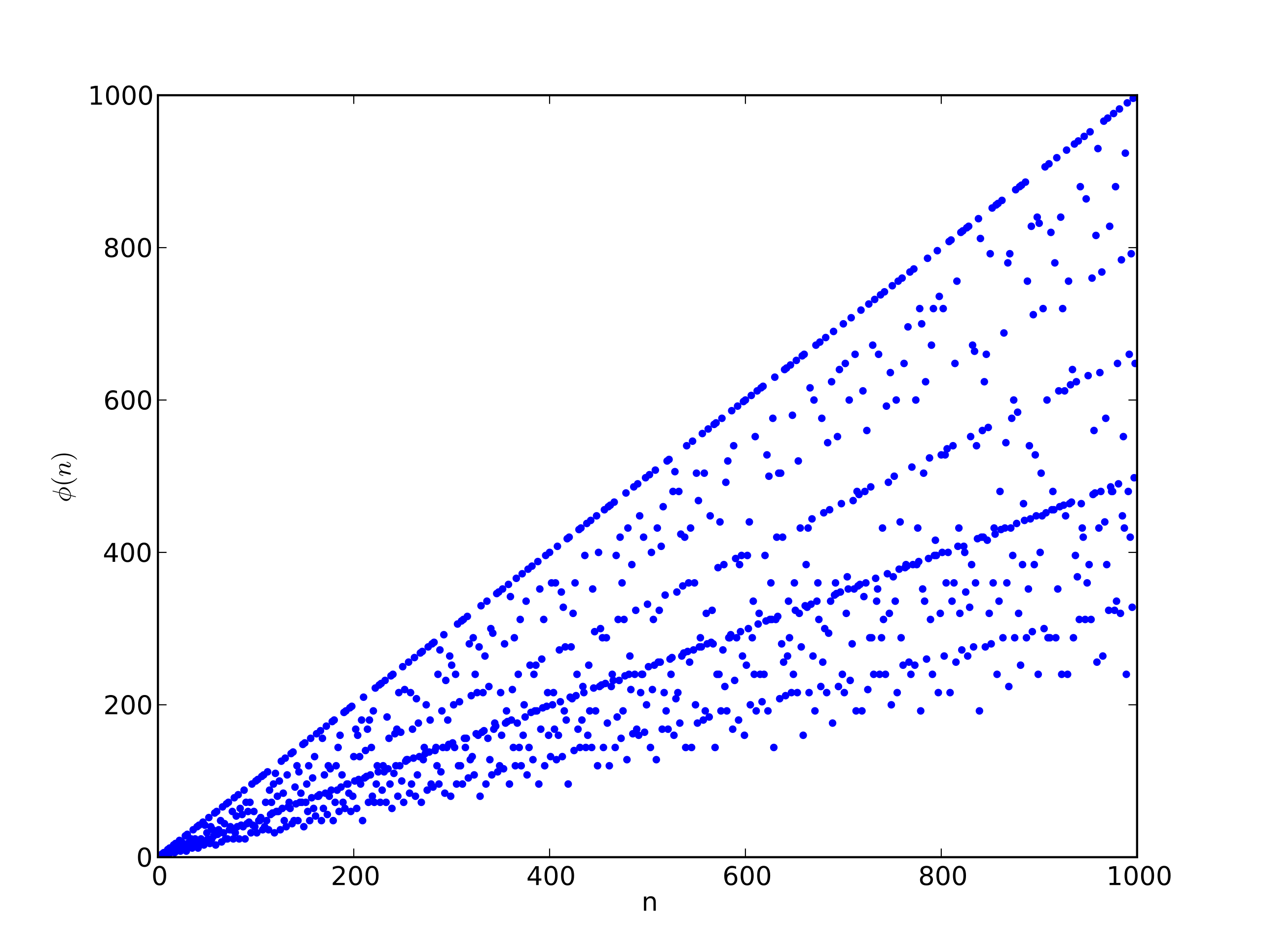

First we introduce Euler’s totient function. Euler’s totient function phi(n) is defined such that phi(n) = the number of positive integers less than n that are relatively prime with n.

Euler's totient function phi(n)

If n is prime, then it’s obvious that phi(n) = n-1 because by the definition of n being prime, it means that none of the numbers less than n divide n. Therefore all n-1 numbers less than n are relatively prime with n.

phi(n) doesn’t have a closed form in general, but we are only concerned about the case when n=N=p*q, and fortunately there is a closed form for that!

We know that p and q are both prime, and we know that phi(n) = n-1 when n is prime. So we know that phi(p) = p-1 and phi(q) = q-1.

How does that help us determine phi(pq)?

Well, we can make use of another theorem called the Chinese remainder theorem.

The Chinese remainder theorem states that for a system of congruences

x = a % n and x = b % m where n and m are coprime

then x exists and x is unique modulo n*m.

Before we prove the CRT, I want to explain how we make use of it. With the CRT, it means that if we choose p and q ahead of time, then we can take any pair of ints (a,b) and map it directly to some value x.

Remember that phi(n) is the number of numbers less than n that are relatively prime with n, and that we care about phi(p) and phi(q) where p and q are both prime. So we can describe sets A and B as A = { 1 <= a < p } and B = { 1 <= b < q }. By CRT, we now know that we can take any pair in AxB and map it to some unique value x modulo pq. But think about that! We have constructed a bijection from AxB to a set C where every element in C is unique modulo pq. In other words, the set C is composed of numbers less than pq and relatively prime with pq. Then |C| is exactly the definition of phi(pq)! And we’ve shown that there’s a bijection from AxB -> C, so clearly |C| = |A|*|B| = phi(pq) = phi(p)phi(q).

Now to make sure we’re good, let’s prove the CRT. We’re going to only prove the CRT for the system of two congruences because that’s all we need.

We want to prove that for the system of two congruences, and assuming n and m are coprime

x = a mod n and x = b mod m

that there is a unique solution modulo m*n.

First, we show that a solution exists.

From the first congruence, x = ny + a for some y. Thus ny + a = b mod m

So ny = b - a mod m

Because gcd(n,m) = 1, this means that we know n has a multiplicative inverse mod m, which we can call n’.

Then n’ny = n’(b-a) mod m

We can cancel n’n because n’n = 1 mod m: y = n’(b-a) mod m. Which can be rewritten as y = zm + n’(b-a).

Plugging this back into the first equation: x = ny + a, then x = m(zm + n’(b-a)) + a

We don’t need to reduce this any further! We’ve now shown that a solution for x exists satisfying both congruences.

Now we need to prove the solution is unique.

Assume x=c and x=c’ both solve the system

Then c is congruent to c’ mod m, ie c ≡ c’ mod m

So c=my+c’, then c−c’=my

So (c - c’) is divisible by m

We can repeat the same line of reasoning for n instead of m, so that (c - c’) is divisible by n

Because gcd(m,n) = 1 then this means that mn also divides (c - c’)

Which means c ≡ c’ mod mn

In other words, x = c and x = c’ implies c is unique modulo mn

So now we’ve proven the Chinese remainder theorem and used it prove that phi(N) = (p-1)(q-1).

Even still, our detour is not yet done. We’ve shown that phi(N) = (p-1)(q-1) but this doesn’t immediately help us make anything out of m^(ed - 1) = 1 mod N.

For that, we need Euler’s theorem. Euler’s theorem tells us that if a and n are coprime then

a^phi(n) = 1 mod n

This is useful because it means that we can now make the equality:

m^(ed - 1) = m^phi(N) = 1 mod N

So now we can equate: ed - 1 = kphi(N) = k(p-1)(q-1) for some k

But before we go further with that, let’s prove Euler’s theorem to be sure.

We won’t bother proving Euler’s theorem in general, we’ll just prove it for when n=p*q where p and q are prime.

That means we need to prove

a^{(p-1)(q-1)} = 1 mod pq

We will solve this by using another theorem called Fermat’s little theorem which really is just a specific case of Euler’s theorem for when n is prime. Fun fact: though named after Fermat, it was proved by Euler!

So let’s focus on proving

a^(n-1) = 1 mod n

when n is prime and a is relatively prime with n.

Let’s start by listing the finite sequence of numbers:

a, 2a, …, (n-1)a mod n

Clearly we have n-1 numbers here. We can also prove that they are all distinct modulo n:

Assume that they’re not distinct! Then there must be j and k such that ja = ka mod n.

This means ja - ka = 0 mod n. Or in other words a(j-k) = 0 mod n.

By our initial assumption that a and n are coprime, then we know n does not divide a. Therefore n must divide (j-k). But since j and k both lie in the range 1 <= x < n, we know that j-k has to be smaller than n as well. Therefore the only value for j-k = 0 mod n is 0. Thus j = k, and so we’ve reached a contradiction, and therefore all a, 2a, …, (n-1)a are unique modulo n.

So this means we have n-1 numbers that are necessarily all in the range 1 through n-1, and they’re all distinct. Then clearly this set is equivalent to the set of numbers 1 through n-1. Thus a2a…(n-1)a = 12…*(n-1) mod n

Rewritten: a^(n-1) * (n-1)! = (n-1)! mod n Since (n-1)! is relatively prime with n, we can divide it out from both sides. Therefore a^(n-1) = 1 mod n. Fantastic!

So now back to the case when n=pq, we need to prove

a^{(p-1)(q-1)} = 1 mod pq

We can rewrite this as (a^(p-1))^(q-1) = 1 mod pq From FLT, we now know a^(p-1) = 1 mod p. But what about modulo pq? Yes, it still works! Because a is relatively prime with both p and q, so multiplying the modulus by q changes nothing about a^(p-1). Therefore we get 1^(q-1) = 1 mod pq. And 1 to the anything is 1, so we’ve proven Euler’s theorem for pq!

Back to finding d

So to recap, we previously found that m^(ed - 1) = 1 mod N, and we’ve now proven that a^{(p-1)(q-1)} = 1 mod N, so now we can move forward by equating ed - 1 = k*(p-1)(q-1)

So here is why it’s easy to find the decryption d for the recipient and hard for anyone else. In order to know what phi(N) is, we have to know p and q. Once we do, we can set the equality: ed - 1 = k * phi(N) = k(p-1)(q-1)

Rewritten: ed - k(p-1)(q-1) = 1 Now we are just two steps away from showing that d exists and that c^d is a unique solution for x^e = c mod N. We’ll use Bezout’s identity to show that gcd(e, (p-1)(q-1)) = 1 and we’ll use another theorem to show that gcd(e, (p-1)(q-1)) = 1 means that a unique d exists for de = 1 mod (p-1)(q-1). So let’s look at these two theorems.

Bezout’s identity tells us that ax + by = gcd(a,b).

This is useful for us because ed - k(p-1)(q-1) satisfies this form and tells us that gcd(e, (p-1)(q-1)) = 1. Knowing that e and (p-1)(q-1) are coprime tells us that e is guaranteed to have a multiplicative inverse mod pq.

Let’s prove those two statements before moving on.

Bezout’s identity states that for two integers a and b with gcd(a,b) = d, then there exist integers x and y such that ax + by = d. We’ll actually prove a slightly weaker version of the identity by assuming that a and b are positive. Given positive integers a and b, we construct the set S {ax + by | x,y s.t ax + by > 0}.

S is non-empty since (y=0, x=1) satisfies the set criterion for all positive a. S also has a minimum d because it is a set of positive integers. We want to show that d is also the gcd of a and b.

To do so, we have to show that d divides a and b, and that for any other divisor c of a and b, c <= d.

Show d divides a and b

We can write the division of a by d as a = nd + r.

Rewritten: r = a - nd.

Remember that d is an element of S, so we can rewrite d as ax + by for some x and y.

Thus r = a - n(ax + by)

= a - nax - nby

= a(1 - nx) + (-ynb)

So we’ve rewritten r in the form of ax + by. We also know r is non-negative because since d is minimum of S, then d <= a so we can always choose a non-negative r satisfying nd + r = a.

But we also know r < d, because otherwise we rewrite a = nd + r as a = (n+1)d + (r-d). Since d is the minimum of S and is positive, then r has to be 0.

Therefore d divides a. We can repeat the same arugment for b.

To show that d is the greatest common divisor, we have to show that for any other c that divides a and b, c <= d. Show c <= d for any other divisor c

Assume c divides a and b. Then a = cx and b = cy. Then for d = ua + vb

d = u(cx) + v(cy)

d = c(ux + vy)

Therefore c divides d, so c <= d.

Thus d is the gcd of a and b.

Now that we have Bezout’s identity, we can prove that a and m being coprime implies that a has a multiplicative inverse modulo m.

Assume gcd(a,m) = 1. Then we know from Bezout’s identity we have ab + cm = 1 for some b and c. Thus ab - 1 = -cm. Therefore ab = 1 mod m.

Now we finally know that d exists and provides a unique decryption when e is relatively prime with (p-1)(q-1). This actually gives us the constraint we need for how to choose e and N. Since p and q are both prime, p-1 and q-1 are both even, which means that e needs to be odd. A possible choice is e=3. Note that if you choose e=3, then you can’t choose any p and q that you want. For example p=19 would break things because p-1 = 18 and 18 is divisible by 3, so we lose the gcd(e, (p-1)(q-1))=1 property, which means we can’t recover m from c^d because c^d might not be unique or d might not even exist.

But how does knowing all this actually help you find the value of d? Fortunately, we have the extended Euclidean algorithm (covered in section below) which tells us how to find the coefficients x and y for ax + by = 1 when gcd(a,b) = 1. If we substitute e for a and (p-1)(q-1) for b, then we can find d in logarithmic time. Remember that an eavesdropper doesn’t know p or q, so they can’t take advantage of this algorithm.

If you didn’t know p and q, then your two options for finding d are:

- trying to find p and q, which will take a very long time

- computing the e-th root of c modulo N, which is actually equivalent to finding p and q

An algorithm for finding d and decrypting your message

So with all this we’ve shown that d should theoretically exist and decrypt c back into a unique message. But we still haven’t covered how. At the beginning of the post, I said that decrypting the message should be hard for eavesdroppers and easy for the recipient. This is possible because the recipient knows something no one else does: p and q.

The extended Euclidean algorithm tells us how to compute the coefficients for ax + by = gcd(a,b). Note that this is Bezout’s identity again.

I’m not going to go as deep on this because honestly I don’t deeply understand why it works.

But the idea is that you define a recursive algorithm on a and b. You basically start by dividing a by b (assuming a is bigger), and keeping the remainder. You then divide b by that remainder, and again, you keep the new remainder. Now you divide the first remainder by the second remainder. And again, you take the remainder from this. And so on until the remainder is 0. Then the remainder before that is the gcd of a and b.

That gives you the gcd, but we ultimately care about the coefficients as well. The extended algorithm, in addition to telling us gcd(a,b), also tells us the coefficients x and y. We don’t just keep track of the remainders each time, but we also keep track of two other variables that we can call s and t. Their sequences evolve like s_{i+1} = s_{i-1} - q_i*s_i. The first couple are defined ahead time as s_0 = 1, s_1 = 0, t_0 = 0, and t_1 = 1. To be honest, I’m not even going to pretend I understand why this works.

But now we can actually implement basic RSA altogether.

Code

import random

def miller_rabin_check(x):

"""

Non-deterministic check whether x is prime or not

"""

ds = x - 1

s = 0

while ds & 1 == 0:

s += 1

ds = ds >> 1

num_bases = 10

bases = [random.randint(1, x - 1) for _ in range(num_bases)]

for base in bases:

m = pow(base, ds, x)

if m != 1:

return False

return True

def generate_prime(bits):

"""

This is a common method for generating large primes for RSA.

Generate a random number with b bits. From there, just keep checking every odd number until

it's prime.

"""

x = random.getrandbits(bits)

if x % 2 == 0:

x += 1

while not miller_rabin_check(x):

x += 2

return x

def create_pq(bits):

"""

We assume for now that we're using e=3 as our public exponent,

so we need to make sure that p and q are relatively prime with 3.

"""

p = generate_prime(bits)

while (p-1) % 3 == 0:

p = generate_prime(bits)

q = generate_prime(bits)

while (q - 1) % 3 == 0:

q = generate_prime(bits)

return p, q

def create_public_key(p, q):

n = p * q

e = 3

return e, n

def create_private_key(bits, public_key):

random_key = random.getrandbits(bits)

e, n = public_key

encrypted_key = pow(random_key, e, n)

return random_key, encrypted_key

def inverse_modulo(e, m):

s0, t0 = 1, 0

s1, t1 = 0, 1

while e > 0:

q, r = divmod(m, e)

s = s0 - q * s1

t = t0 - q * t1

m = e

e = r

s0 = s1

t0 = t1

s1 = s

t1 = t

gcd, s, t = m, s0, t0

return gcd, s, t

def decrypt_msg(msg, p, q):

e = 3

phi = (p-1) * (q-1)

_, _, d = inverse_modulo(e, phi)

if d < 0:

d += phi

original_msg = pow(msg, d, p*q)

return original_msg

def rsa():

asym_bits = 512

sym_bits = 256

bob_pq = create_pq(asym_bits)

bob_pub_key = create_public_key(*bob_pq)

alice_private_key, alice_encrypted_private_key = create_private_key(sym_bits, bob_pub_key)

bob_decrypted_alice_key = decrypt_msg(alice_encrypted_private_key, *bob_pq)

assert alice_private_key == bob_decrypted_alice_key

rsa()

Practical caveats

This is pretty much the most basic version of RSA that we can get. In reality, we have to do some extra work.

Wikipedia provides a nice list of some attacks against basic RSA.

Caveats to choosing N

In practical details, there are some extra constraints around p and q because there are several tricks that make factoring N easier under certain conditions. Stack exchange provides an example.

How does one choose p and q though? For modern security, N needs to be at least 1024 bits. This means that p and q should be roughly 512 bits each.

But these numbers are still massive. It would take a while to generate and determine whether they’re prime.

NIST publishes prime numbers, so maybe we could use those. But this is still problematic. If you used a public and pre-generated list, then suddenly the search space would be very small and it wouldn’t be hard for an attacker to find p and q.

In reality, there does not exist such a list for 512 bit primes. Instead, there is an algorithm to generate large primes. This stackexchange answer does a great job of explaining.

Essentially, you are likely to find a candidate prime after less than 200 tries starting from a random 512 bit number. So that’s very quick, to generate one, but to generate all of them, you’d need to do it 2^512 times which is unbelievably huge. (If you protest that this number includes small primes like 3 and 5 technically, then you can fix the largest bit to 1 and check for the remaining 2^511 options)